Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 42

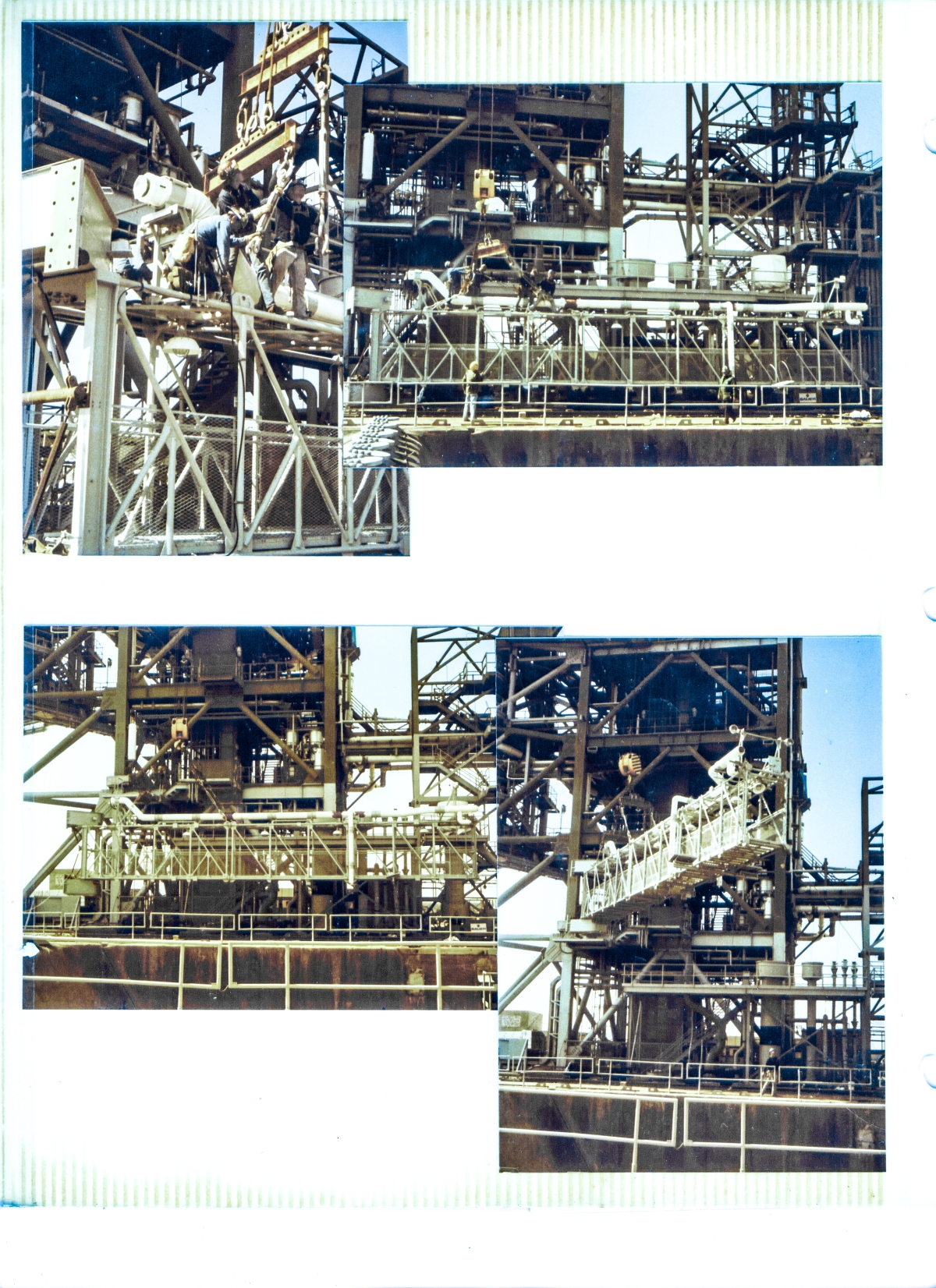

GOX Arm Lift 1 (Original Scan)

Top photographs show the ironworkers hooking things up, and in the bottom two shots the lift gets underway. Note that the Vent Hood, or Beanie Cap, is not installed. That went on later as a separate operation. The GOX Arm was a nightmare for us, and some of the stuff that went on during our attempts to assemble the thing down in the Flame Trench were almost beyond belief. Suffice it to say that the arm went up and was hung on the tower, and then it came back down again. I'm pretty sure this is the first lift, but I cannot be absolutely certain. Cost us a bundle in wasted time and effort, as a result of less-than-sterling engineering. I wound up writing what a few people took to calling "The pitchfork letter" and in the end we got compensated. But it was, shall we say, interesting, while it was going on. Fortunately, the lift itself went as smooth as silk.

Top Left: (Full-size)

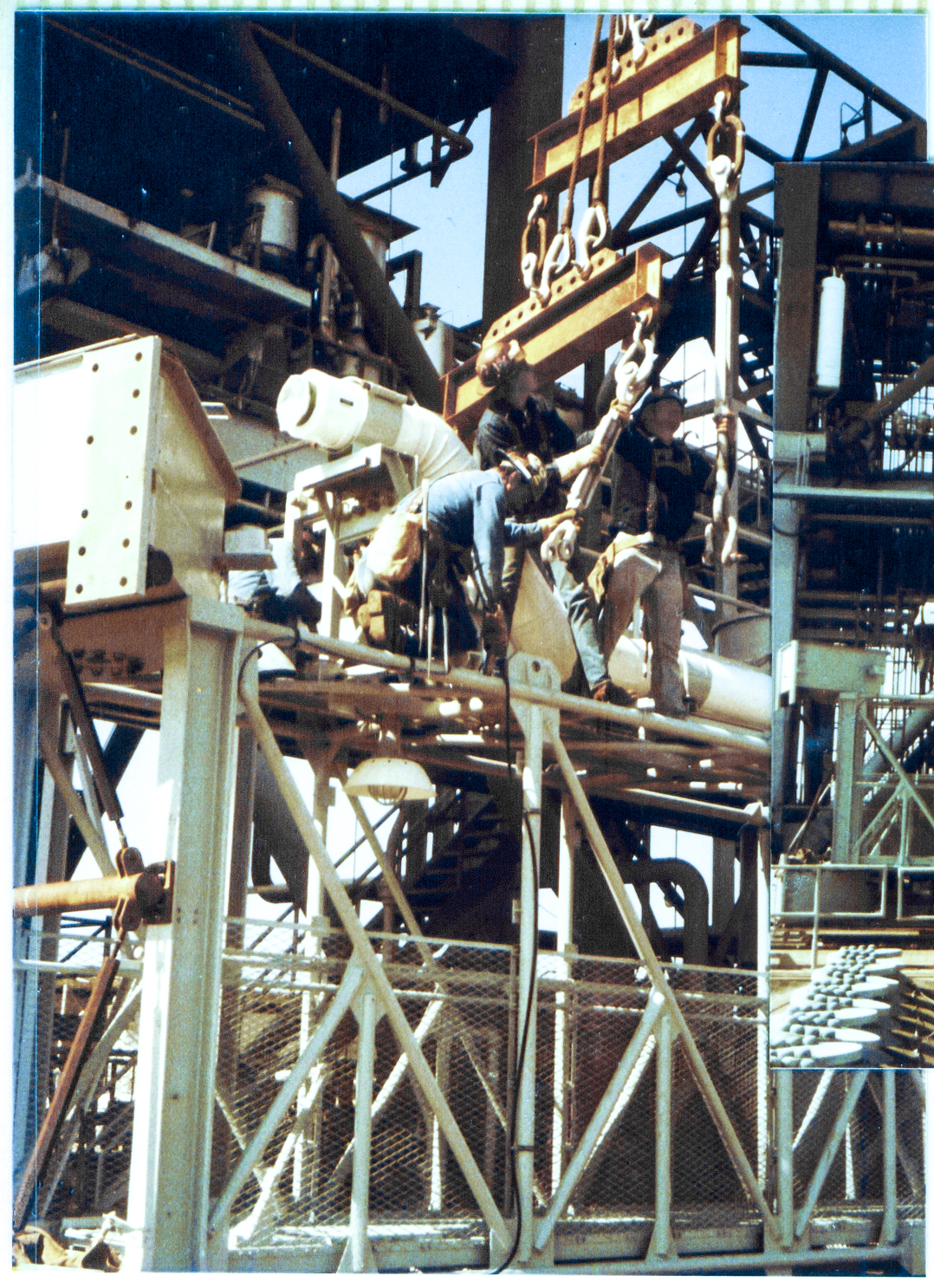

We have previously dealt with the strongback upon which the Gox Arm is attached to the FSS, and now it is time to deal with the arm itself.

Union Ironworkers.

Heavy gear.

Not so heavy that it could not be manipulated by hand, but we're getting there.

People think rockets are all white lab coats, polished surfaces, and bright fluorescent lighting, but that is definitely not the case.

Rockets are heavy gear, and the business of getting them off the ground and up above the atmosphere where you want them to go, involves a tremendous amount of very gritty, grimy, hard labor with hard equipment down on the ground ahead of time.

And here you see an excellent illustration of that end of things as a team of four ironworkers attaches the lifting gear which will be required to get the GOX Arm just a little bit less than a full 250 feet up into the air, directly above them, where it will be attached very near the top of the Fixed Service Structure, which looms darkly in the top left portion of this frame. (And please note that most of the far right portion of this frame is actually an overlapping separate photographic print from the main scanned image at top, taken from the photo album, which I chose not to crop out in the interests of letting such detail as can be seen above and below it in this image, remain visible.) Without which Gox Arm, the Space Shuttle would never be able to claw itself into space in the first place. Would never climb above the atmosphere. Would never go anywhere.

So yeah.

So heavy gear.

Pear links, shackles and shackle pins, turnbuckles, clevises and clevis pins, spreader beams, lifting lugs, lifting slings, wire rope, wire rope thimbles, swaged fittings, stiffener plates, hot-dip galvanizing... ironworker stuff.

Without which, in advance, no rocket will ever fly.

In this frame, the 65-foot long Gox Arm Truss remains on its temporary support stanchions, directly in front of the FSS to the west of the Flame Trench on the pad deck, and is being prepared.

Top Right: (Reduced)

And in this frame I've stepped back away from the work, across to the far side of the Flame Trench, and down in the bottom left corner of the frame, you can see the row of SSW Spray Headers that line the crest of the Flame Deflector.

At the foot of the FSS, the work goes on.

The Gox Arm remains on its support stanchions, and by this time all of the rigging had been properly attached to the lifting points on the truss, and our crew of ironworkers is now in the process of directing the crane operator to, very slowly, come up on his load, and as the assembled lifting sling begins to rise and begin to straighten out and assume its final orientation, and come into tension, the ironworkers stay right on top of all of it, hands-on, making sure nothing snags, nothing hangs up, nothing gets kinked or otherwise gets out of proper alignment, and everything is just so, just as it should be, prior to coming taut and pulling the weight of the truss into the air.

As we have previously mentioned with the OAA, most of the weight of the truss is in the hinge boxes, and for that reason, the center of the lift is offset quite a bit in that direction to keep the arm level as it goes up.

Behind the truss, from left to right, you can see the bizarre complexity of the FSS, the MLP SSW Access Platform, the West MLP Access Stair Tower, MLP Mount Pedestal, and a bit of the 9099 Building, along with all the associated handrail, stairs, main structure, diagonal bracing, flip-up platforms, piping, ducting, cabling, hypergol scrubber, and all the rest of it, too.

Just above the dark top margin of the shadowed west wall of the Flame Trench which runs along the bottom of the frame, beneath the removable handrail, the Side Flame Deflector locking lugs can be seen. On launch day, the SFD on this side of the Flame Trench (and the other side, too) would be relocated right here, locked down with heavy steel pins through the locking lugs, and it would be blocking our view of everything else that we're able to see here.

Bottom Left: (Reduced)

The weight of the Gox Arm Truss is no longer borne by its support stanchions, and it is now suspended by the Hammerhead Crane, just above the pad deck.

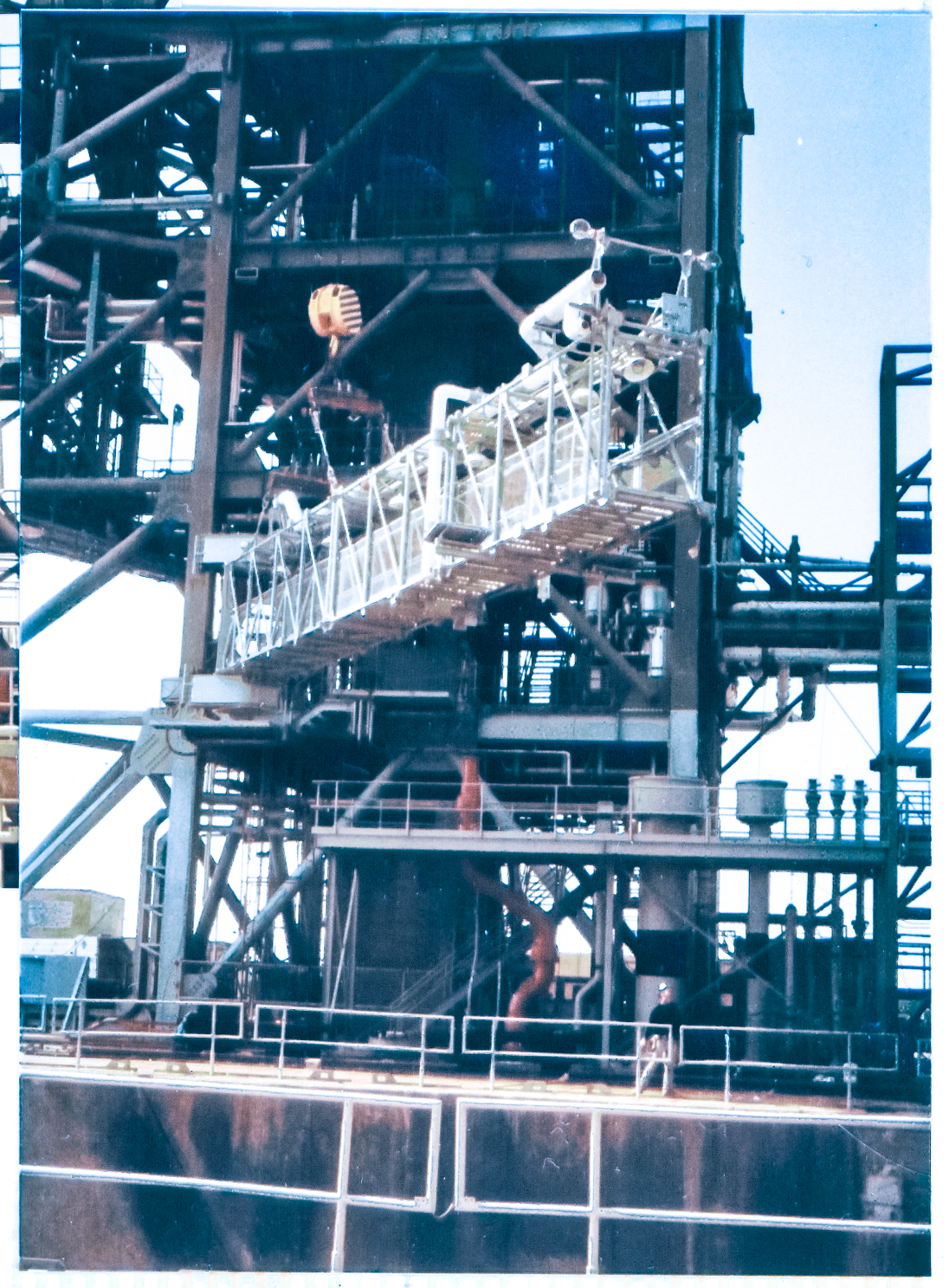

This is one of the very few times we used the Hammerhead Crane for anything at all. Despite its substantial appearances, the Hammerhead Crane was only rated for 10 tons at the far end of its reach, which, on top of that, failed to extend far enough away from the centerline of the FSS to perform very much useful work at all, for the purposes of constructing Pad B. So for the most part, it just sat there, and nobody used it.

Boeing's TTV people would periodically test it, spin it around, and verify it remained in good working order, but that was about it. Interestingly enough, if you were up on top of the RSS, say maybe up on the roof of the RCS room investigating the ET Access Platform Winches following a scary event with those winches, and Boeing decided to swing the Hammerhead Crane around, starting, stopping, and restarting it through its various rotational positions, it would impart a significant amount of torsion into the FSS, and you could feel it flex the entire set of structures as it did so. The RSS would move back and forth laterally a little bit, and it would move enough that you could feel it move. And yeah, that was an attention-getter whenever it happened.

In this frame, the Gox Arm is no longer in contact with the ground, and it's being given the standard set of critical inspections that you give large objects just before you begin lifting them to their destinations.

Everything must be right. Everything has to work.

Lifts are some of the most dangerous operations in all of construction.

People do the best they can. People do not want to see things fail. People do not want to see their coworkers or themselves getting hurt or killed.

But lifts have a way of testing your skills, via trial by fire, and although it's rare, sometimes things do happen, and if they do, more often than not, they will happen during a lift.

So you be good and goddamned sure of things before you start going up with something as substantial as this.

Bottom Right:

(Full-size)

And now that everything has been checked and verified to be in good order, with the arm clocking around toward the orientation it will assume when it gets bolted to the tower, we're on our way up, on our way to the top of the FSS.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |